China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2004/Jul

Father Alberico Crescitelli a martyr to incredible and unproven accusations

Recently, the Holy Spirit Study Centre published a book in Chinese and English, written by Father Gianni Criveller, entitled, The Martyrdom of Alberico Crescitelli, Its Context and Controversy. Of all the 120 China martyrs canonised by Pope John Paul II on 1 October 2000, none evoked more controversy from the government of the People’s Republic of China than Alberico Crescitelli. Following is a brief overview of the saint’s life. The book makes very interesting historical as well as inspirational reading, and is available at the Holy Spirit Study Centre and the Catholic Centre in Central.

Alberico Crescitelli

Alberico Crescitelli was born the fourth of eleven children on 30 June 1863 in Altavilla Irpina, Avellino province, in the diocese of Benevento, Italy. In 1880 he entered the Pontifical Seminary of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul. He then studied at the Gregorian and St. Apollinaire Universities and was ordained a priest on 4 June 1887, in Rome, returning to Altavilla to say his first Mass. He spent a few months in the town of his birth assisting both the sick and those dying from cholera, then left Italy in the spring of 1888, for a mission in Southern Shaanxi, where he arrived in August of the same year.

For 12 years Crescitelli worked in the Vicariate’s various villages. His superiors considered him an excellent missionary, devoted and hardworking, with unostentatious but deeply rooted virtues and qualities.

Killed by the Boxers?

The assassination of Father Crescitelli is generally blamed on the Boxer Upspring of 1899-1900. However, original documentation, both ecclesial and Chinese, proves that it was not the Boxers who killed Father Crescitelli. In fact the Boxers never spread as far as Shaanxi province.

The link between Crescitelli’s martyrdom and the Boxers’ revolt consists in one single element: Crescitelli’s enemies came to hear about the July 5 imperial decree and used it to cover their crime. The Boxers were blamed for acts they never did.

Controversies on the occasion of Crescitelli’s canonisation (2000)

When the Chinese martyrs were beatified (1893, 1900, 1909, 1946, 1951, 1955, and 1983), the Chinese government never protested nor did it mention any crimes committed by them. However, on the occasion of the cumulative canonisation of the 120 martyrs on 1 October 2000, the authorities of the People’s Republic of China strongly opposed the canonisation, accusing the missionaries of having been the instruments of colonialism and imperialism.

In certain publications Guo Xi-de (Crescitelli) was singled out as a criminal who practised the infamous jus primae noctis where “all the girls who came to him were abused and raped” before their marriages. He was also accused of having abused the wives of local people. In actuality there never was any such thing as the jus primae noctis. History now shows that this was a legend even in medieval Europe.

The Historical Documents and the PIME (Pontifical Foreign Missions Institute) sources indicate that Crescitelli was murdered after a conflict with the local gentry, when aid was being distributed during the famine of 1900.

Crescitelli’s assassination according to The Historical Documents (Chinese sources)

The dynamics of Crescitelli’s death described in The Historical Documents coincide with the story of his martyrdom as described by biographers from PIME and the Positio. (…) We know how Crescitelli died. It is a pity that the government authorities in China, although provided with sources such as The Historical Documents, instead used radically prejudiced literature for their attack on Crescitelli.

The following extract from The Historical Documents describes Crescitelli’s assassination.

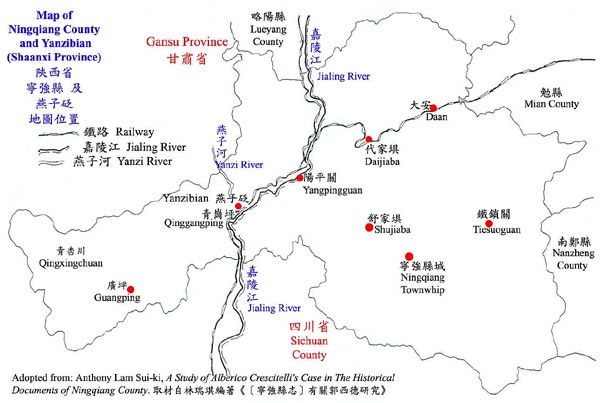

At nine in the evening of July 20 over 300 people led by Rong-dong, Teng Shang-xian and Yang Hai, (…) carrying lit torches, armed with long swords and lances, met in Yanzibian looking for Guo Xi-de (Crescitelli).

Guo Xi-de was frightened and had fled to the office of the tax collector, Yao Chi-zhang. At nine o’clock that evening, the crowd ran to the front of the offices belonging to the tax collector shouting: ‘capture the foreigner’. Yao said to Guo Xi-de: ‘You see how many they are. I cannot stop them. The only thing you can do to save yourself is to flee. So Guo Xi-de went to the backdoor. There the crowd of enraged peasants took him; he fell to his knees and prayed. Guo Xi-de said: What have I done wrong? Take me to the government office.’ But the crowd did not listen to him. And they hit him with their swords and lances. His left arm, nose and mouth were wounded. They tied his hands and feet and carried him to the main road in Yanzibian. At dawn the following day, Guo Xi-de was killed on the banks of the river Jialing, and his body was thrown into the river.

Crescitelli’s martyrdom according to the Positio

What follows is a greatly abbreviated report according to the Positio:

Father Crescitelli had by now passed the Jen-tze-pien (Yanzibian) when the customs-official Mandarin, (…) begged him to desist, pointing out to him the dangers he would encounter. Father Crescitelli, accepted his offer of hospitality, (…)

But what betrayal in that offer of help! (…). As soon as darkness fell repeated shots were heard and immediately afterwards a large crowd of people appeared from every corner, (…) shouting angrily and calling repeatedly for the European. The (…) official, his face hypocritically pained, addressed the missionary: It is impossible for me to defend you against so many; the only hope, if possible, is the secret backdoor. (…) He pointed out the door and left him. (…)

As that crowd of assassins advanced, (…). the poor Missionary, terrified (…) said: ‘Why are you doing this? What have I done wrong? What do you want of me?’ (…) As he spoke, one of the most bloody and infuriated among them, hit him on his left arm, almost cutting it off. At this first signal of the massacre, all the others (…) wounded him with their knives and sticks while one of those most angry lifted a large sword and dropped the blade on his head to open it totally.

(…) They stripped him of his cassock and tore his other garments so badly that they were no longer sufficient to cover his nakedness. (…)

Unable to walk, unable even to stand, one of those standing nearby was obliged to carry him on his shoulders. (…)

(…) They deposited him in an area where there was a dilapidated house next to the street, and they scattered to neighbouring taverns for merrymaking.

(…) When dawn broke, those still able to reason gathered in a council (…) and established definitely that the foreigner and his followers should be killed. (…)

The high sun announced that is was close to midday and the leading instigators hastened to carry out the dreadful execution.

Repeated blows fell between his head and his neck without however beheading him; until exhausted, two people held the instrument, one at each end using it like a saw until his head fell to the ground.

The sacrifice had been made, (…) [and] threw those venerated limbs among the waves to cancel all trace of this massacre. (…)

Moral conviction as regards to Crescitelli’s innocence

(…) The accusations brought against Crescitelli are not founded on any independent and credible documentation. They are conflicting and incredible from a historical point of view. Crescitelli’s confreres, who had known him well and for many years, started his beatification cause in 1908, only eight years after his death. The testimony provided by the confreres was unanimous about the holiness of Crescitelli’s life.

At the Vatican, in St. Peter’s Basilica on 18 February 1951, Pope Pius XII declared Alberico Crescitelli “blessed”. The pope’s speech was memorable especially for the passage in which he described Father Alberico’s martyrdom:

“Humanly speaking, his death was horrible; perhaps one of the most atrocious recorded in history. Nothing was missing, neither the cruelty of the torments, nor the time they lasted, the most barbaric humiliations, nor the suffering of the heart, nor the hypocritical betrayal of false friends, nor the hostile and threatening screams of his murderers, nor the darkness of being abandoned.”

Pope John Paul II included him in the list of 120 martyrs of China who were canonised in a ceremony at St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican, Rome. Their feast day is on 1 October 2000.

ENG

ENG