China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2010/Aug

Better earthly cities, but not the heavenly Jerusalem

‘Is it God’s holy will for the majority of children to be born in poverty and to die before reaching adulthood?’ ‘Yes, that is God’s holy will.’

‘Can we afford to have a second baby?’ ‘No, this apartment is too small’

Over the centuries, people have asked questions that those in another time and place would not dream of asking and have given answers that others cannot believe.

The west in the so-called Good Old Days

Life in ancient times was no fun. Old cemeteries are full of small coffins. Adult skeletons often contain only a few teeth and show deformed bones from malnutrition and hard physical labour. Although the phrase “struggle for existence” was not coined until the mid-19th century, everyone knew life was hard for almost the entire population.

When a new religion appeared in the Roman Empire, people said, “See how these Christians love one another.” Even though the new faith was illegal and intermittently persecuted, people were still attracted. They wanted to acquire brothers and sisters who fed the hungry, cared for the sick during epidemics and buried the dead. The early Church was a hope and a refuge in a hard and heartless world.

Enforcing a brutal penal code, the Roman Empire eliminated pirates at sea and kept highway robbers to a minimum for 450 years. As it collapsed, life got worse. St. Augustine (354-430 AD) reflected on the growing chaos when he wrote The City of God. He used Original Sin to explain the hardships of life and the human inability to create a just society. Perfection cannot be found in building the City of Man, but rather lies at the end of a pilgrimage to the City of God. Christian life is a disciplined preparation for the fullness of the life of the world to come.

After the Dark Ages, western civilisation slowly recovered. The 13th century was relatively peaceful and prosperous. But the 1300s were marked by cold weather, failed harvests, war and the Black Death (bubonic plague).

Historian, Barbara Tuchman, titled her survey of that age A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century.

A popular Marian hymn from that era was the Salve Regina. “Hail Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy … to thee do we cry, mourning and weeping in this valley of tears.” Life was harsh and people had repeatedly failed to make lasting improvements in the human condition. Both popular sermons and scholastic theology were written to give comfort and practical advice in an environment of learned helplessness.

China in the so-called Good Old Days

Chinese history is filled with internal rebellions and foreign invasions (內憂外患). Epic battles with swords and spears make for entertaining cinema, but were terrible on the ground in realtime.

When the country was prosperous and the people at peace (國泰民安), much of the credit went to honest and hardworking officials who aimed to govern for the benefit of the people (經世濟民). In the mid-18th century, when Old China reached its peak, people proudly said the Qing (清) Dynasty “shone with the splendour of the sun at noon.” Yet some people whispered “one minute after noon, the sun begins to decline.”

If we had statistics, life expectancy and literacy in China in 1755 would compare poorly to the numbers in 1955, let alone in 2010. The burdens of malnutrition, ignorance, illness and premature death were heavy in China and in every other nation on earth until recent generations.

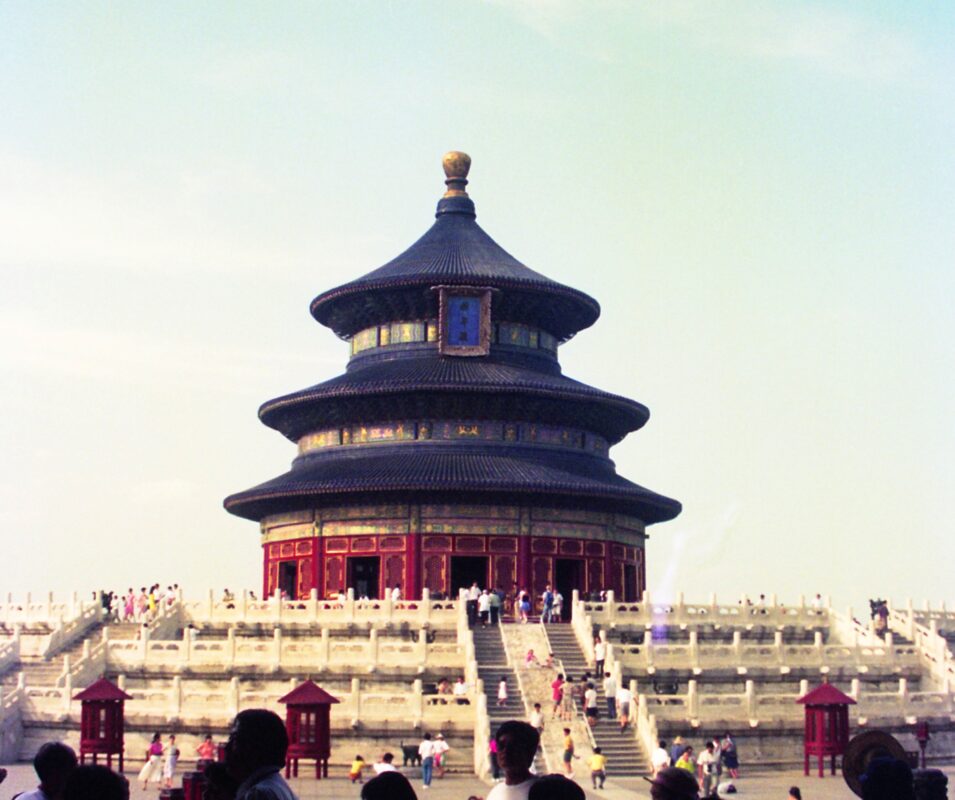

Birth, old age, sickness and death all involve suffering. Buddhism offers an explanation for suffering and a path to eliminate its underlying cause, desire. That faith spread from India and took root in China. This world was described as merely red dust (紅塵). The moral of many Chinese stories is that the focus of life should not be material, but rather spiritual development. China’s most famous novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢), was written in the mid-18th century. On the opening page, a heavenly stone begs to be incarnated on earth for a tour of the red dust and his adventure begins.

Building a better world

The reader already has a general idea of the progress of science and technology during the past few centuries, as well as improvements from political and economic reforms. The future kept looking brighter and brighter until 1914, when World War I erupted and faith in western civilisation was shaken.

One result of the subsequent wars and revolutions was the founding of New China in 1949. The goals were to end the exploitation of people, develop science and technology, and revive the nation.

The Second Vatican Council met from 1962 to 1965 to look at the “signs of the times.” A key document of the council, The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), urged Catholics not to lose sight of either heavenly or earthly objectives: “In their pilgrimage to the heavenly city, Christians are to seek and value the things that are above; this involves not less, but greater, commitment to working with everyone for the establishment of a more human world” (n. 57). The traditional corporal and spiritual works of mercy encouraged Catholics to help their neighbours; Vatican II adopted a more optimistic view of improving the world as a whole.

Different dreams in 1966

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution began. The dream of permanent revolution quickly turned into a nightmare for the whole nation. After a wasted decade and fruitless efforts to smash all that was old and traditional, China turned towards economic and scientific modernisation.

Echoes of the Rainbow (歲月神偷) is a recent award-winning movie. Set in 1966 or 1967, it depicts a poor family raising two boys in Hong Kong. They listen to the radio, since no one has television. Only one shop on the street has a telephone. The flats lack air-conditioning, so people eat outdoors and talk to their neighbours at mealtime. The movie takes a sad turn, yet people in early 2010 praised the film for showing how the previous generation had worked hard without giving up. Some commentators asked, “What’s wrong with young people in Hong Kong today?” However, none of them answered, “television, air conditioning and computers.” That would make prosperity and new technology sound like causes of the problem.

In 1966, a television documentary, filmed in a rich suburb of the Unites States of America, created an uproar. The narrator in Sixteen in Webster Groves said, “They are 16-years-old. They live in Webster Groves, Missouri. They are children of abundance, of privilege, of the good life in America. But is something missing in their lives?” Several times during the hour-long programme, he asked, “What if the dream comes true?”

The teens came across as materialistic, conformist and shallow. There was a quote from Ecclesiastes, “Vanity of vanity, all things are vanity!” Parents who had eagerly awaited seeing their children on national television were outraged. They had worked hard to give their children everything, but the documentary implied that the Great American Dream was empty and vain, a chase after the wind.

What if the dream comes true?

Millions of mainlanders have become wealthy, a good portion of the population now enjoys a middle-class standard of living and everyone dreams about becoming rich. The middle-class in China has grown from 15 per cent of the population in 2001 to 23 per cent in 2010. One projection says that 700 million Chinese will be middle-class by 2020, or 48 per cent of 1.45 billion people.

Yet problems remain in the quality of education, social security and promoting social responsibility, rather than greed and selfishness.

City living is expensive. Mainlanders complain about being house slaves (房奴), who spend all their money on rent. One bitter observation in our city says, “In Hong Kong, the most effective form of birth control is high rent.” The gap between rich and poor, old city families and rural migrants, enrolling children in the best schools and paying for after-hours tutoring, the need to impress neighbours with a big car and upscale clothing – all of these add to the stress of urban living.

One participant in a popular mainland television programme on dating and romance recently got more attention than she expected. All the women said they wanted a rich boyfriend. A boyfriend with luxury car is even better. The young men complained about the unrealistic demands of their girlfriends. Then one woman said “I’d rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle.” The government told the station not to be so vulgar.

Aside from the fact that bluntly advertising her materialistic standards is hardly the way to catch a boyfriend, what if her dream comes true? Suppose one day she is crying bitterly in the back seat of an expensive car, looks out the window, and sees a poor woman smiling on the back seat of a bicycle? Would she regret making that statement on television?

Help for society in Catholic teaching

The Catechism of the Catholic Church was published in 1994. It applies both traditional and Vatican II teachings to contemporary life.

The catechism applies the seventh commandment against stealing to cover “business fraud, paying unjust wages; forcing up prices by taking advantage of the ignorance or hardship of another” (n. 2409).

It claims the Church has a right to speak in the public arena about social questions. “The Church is concerned with the temporal aspects of the common good, because they are ordered to the sovereign good, our ultimate end” (n. 2420).

Those who claim that faith is purely a personal affair are offended by such talk. Yet the Chinese government now admits different religions have a part to play in constructing a harmonious society. As China continues to urbanise in the coming years, to what extent will Catholic social teaching be allowed to help build better earthly cities?

MJS

ENG

ENG