China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2014/Sep

Why were they willing to suffer?

On 1 October 2000, the Church canonised 120 Chinese martyrs. The 76 lay people, eight seminarians, seven religious sisters, 23 priests and six bishops represented the many Chinese and missionaries (Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox Christians) who died professing their faith between the 17th and early 20th centuries, notably in the provinces of Hebei, Shanxi, Sichuan and Guizhou.

Some friends and I recently had the chance to visit some martyrdom sites in Hebei, northern China.

The word martyr, from the Greek martus, means someone who testifies based on knowledge from personal experience.

The apostles, who lived and ate with Christ and followed him closely during his ministry, called themselves witness of his resurrection (Acts 1:22).

But from the beginning, to bear witness to faith in Christ has been an act that carries some risks. Refusal to worship the gods of the state, whether the Roman pantheon or other ideological tools designed according to the times, was considered treason. And treason was in most cases punishable by death.

The dissolution of imperial rule and the birth of modern China is a vast historical subject. In a sense, the transition is still ongoing. The death of the Chinese martyrs took place against this volatile background. Tracing the footsteps of a 14-year-old girl, St. Anna Wang, may help us reflect on the contemporary meaning of discipleship.

It was the twilight of Manchu rule (1644 to 1911). In provinces in the north it had been a year of severe drought and crop failure. Villagers who had no work were attracted by martial groups claiming cultic powers that would render practitioners invulnerable to western firepower. They began to rally under the slogan, Support the Qing, destroy the foreign.

China was losing one humiliating battle after another. Peace was bought only temporarily by huge sums of money and unequal treaties. For example, the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, which ratified Hong Kong as a British colony; and the Treaties of Tianjin (1858), which opened more treaty ports to foreign trade, legalised the opium trade and allowed the establishment of permanent diplomatic legations in Beijing.

The country was being carved up like a jigsaw puzzle into multiple spheres of influence where foreign nationals enjoyed additional privileges and sometimes extraterritorial rights above local law.

The treaties also gave Christians the right to proselytise in China. Christianity had been outlawed since 1721 and missionaries saw this as a chance to bring the faith back to the country.

Some rode on the coattails of their nation’s military and diplomatic powers. Many Chinese lumped missionaries with foreign invaders. Christians, especially Catholics, were hated as a special interest group.

Foreign powers, threatened by rising violence, demanded the suppression of martial groups known as the Boxers or 義和團 (united in righteousness). Cixi, the empress dowager, once more seized power by putting the reformist emperor, Guangxu, under house arrest.

The Qing government had no policy. It tried to placate the foreigners. But often it was up to the local officials to disband or foster the Boxers. Those close to Cixi were in favour of whipping up nationalist sentiments and grooming the Boxers as a deterrent against foreign influence.

On 21 July 1900, the Boxers raided the village of Majiazhuang in Weixian. They arrested some Catholics, including 14-year-old Wang; a young mother, Lucia Wang; and her nine-year-old son, Wang Tianqing. A parish elder, Joseph Wang Yumei, was summarily executed.

They took the prisoners to a large courtyard and ordered them to choose between freedom and death. “The imperial court forbids foreign religion,” they claimed. “If you renounce the faith, come out of the east room and enter the west room where you will be released.”

Wang’s stepmother did. She pulled on her daughter’s arm, but she clung to the doorframe, proclaiming, “I believe in God. I am a Christian. I will not recant my faith.”

As dusk fell, some Boxers lit candles they had stolen from the church. Anna told her companions, “See how glorious and beautiful these candles are from our church! But the glory in heaven is 10,000 times more.” Then they prayed their evening prayers together.

The next morning, they were taken to the execution ground. Young Wang again led them in prayer. They said the act of contrition.

When some non-Christians offered to adopt her son, Lucia Wang, the young mother, said gently but firmly as she held her son close to her, “I am a Christian. My son is also a Christian.” Mother and son were killed along with other women and their children.

Anna was the last. Kneeling, she prayed aloud, her face was radiant. Witnesses said she did not look like someone about to be executed. Rather she seemed to be getting ready for a celebration. Her dress was tidy. Her hair was neatly braided.

The executioner hesitated, “Why don’t you renounce your faith?” Then he tried to bribe her, “If you do, we will find you a rich husband and you will live a good life!” Anna pointed to a church in the distance. “I am already betrothed,” she replied.

Furious, the executioner slashed at her shoulder. Refusing to yield, she was finally beheaded. The bodies of the martyrs were recovered 15 months later and buried with care. Through her intercession, her family repented and returned to the faith.

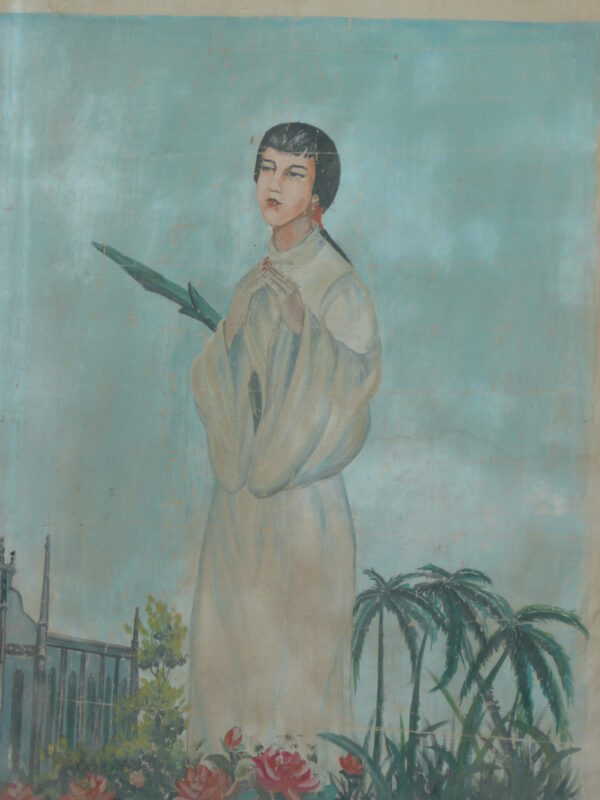

A picture of St. Anna Wang, young and resolute, holding a palm branch that represents the victory of martyrs, now hangs in a local church. A more intimate portrait graces the wall of the home of her great-grand nephew, across the room from an old photo of several generations of the family taken in the turbulent 1960s.

Faith lives on in the family.

We knew we were walking on sacred ground as we threaded our way through the village. “But why?” I found myself asking. Many of the martyrs were so young. Why were they willing to give up their lives? What made these Christians willing to suffer for their faith?

Perhaps the words of St. Paul speaking about early Christians offer some clues:

We are subjected to every kind of hardship, but never distressed; we see no way out, but we never despair … Indeed, while we are still alive, we are continually being handed over to death, for the sake of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus, too, may be visible in our mortal flesh (2 Corinthians 4:8-11).

As Paul explains, everyone who follows the footsteps of Christ is familiar with death. Every day we live and every choice we make can be a willing sacrifice. But are we masochists? Do we inflict pain on ourselves for the sake of pain?

No, we make that choice – sometimes the choice may be inconvenient or against conventional wisdom – by sacrificing our ego. As Christ sacrificed himself on the cross for us, so we die to our old selves for the sake of Christ.

But the choice for Christians is not about death. For we believe in – and testify to – the life of Jesus Christ. Paul reminds us that our life and death both have a purpose – “so that the life of Jesus, too, may be visible in our mortal flesh.”

How does our mortal life – a life that is full of limitations – bear witness to the life of Jesus? We find the answer among contemporary witnesses in China, not unlike the martyrs before them who freely gave their lives.

Those who assert that Christianity is foreign to Chinese culture, fail to grasp how deep the faith is where it has been planted and how much good is being done for the nation because of faith in the life of Jesus!

China has been modernising with a vengeance. Now the world’s second largest economy, China has made huge progress. At the same time the country is torn by great disparity and social injustice.

In small towns and rural areas, the young have moved to cities in search of work. The old and the young are left behind. Children grieve for their parents and grow up practically unsupervised.

Like many places in the world, virtual reality and the Internet take the place of personal relationships. When family relations are weakened, is it a surprise that the sick, the handicapped, the elderly people and female children are abandoned, sometimes literally on the streets?

Pope Francis has been warning against a throwaway culture. He criticises a global economic model that is based on exclusion and inequality saying, “Such an economy kills… Human beings are themselves considered consumer goods to be used and then discarded” (Joy of the Gospel, 53).

Pope Francis goes on to affirm the identity of Christians. “We Christians remain steadfast in our intention to respect others, to heal wounds, to build bridges, to strengthen relationships and to “bear one another’s burdens” (Galatians 6:2) (67).

In mainland China, we met brothers and sisters who faithfully tend to their flocks. We were amazed to see young people with disabilities thrive and elderly people whose faces light up with hope! Young people, students, including non-Christians, are inspired to care for and spend time with those who are on the margins of society. This is the good news in action!

The physical, financial and psychological burdens of providing care are real. Faced with many hardships, why are these Christians willing to bear one another’s burdens?

That reminds me of the original sense of martyr – one who bears witness based on lived experience. The blood shed by the Chinese martyrs is precious.

Likewise, the blood and tears are shed daily, so that lives in darkness and without hope can be transformed into miracles of new and shared life – that is a powerful witness to Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection!

What price are you and I willing to pay for our faith?

CP

ENG

ENG