China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2017/Jul

Nestorian Crosses of the Silk Road

The advocacy by the president of China, Xi Jinping, for the One Belt, One Road initiative has revitalised interest in topics related to the Silk Road. One of the most eye-catching has Christian relevance: the Nestorian Crosses found in Ordos, Inner Mongolia in China.

Andrea Chen Jian, a young scholar at the University of Hong Kong describes them in this way, “The Nestorian Crosses are perceived as significant materials not only for Silk Road studies, but also for the study of Chinese Christianity, especially in light of the current poor availability of historical data of Jingjiao (景教)” (Chen 2017, p3).

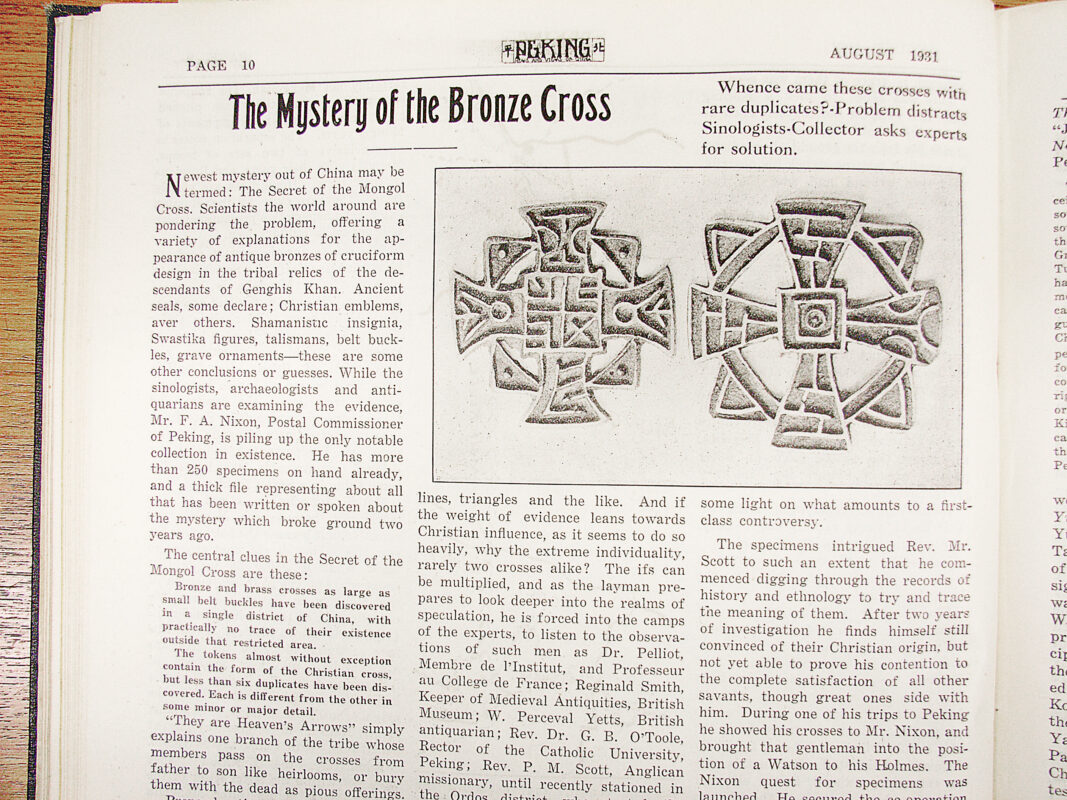

Nestorian bronze crosses were cast in the Ordos region in north-west China (Inner Mongolia) during the Yuan dynasty (1272 to 1368). They measure between three and eight centimetres in height are flat, plaque-like ornaments with an outline in high relief and a loop on the back suggesting that they were used as personal seals worn on the body.

The loop facilitates strapping to human clothing or girdles. The fine motifs of the cast Christian and Buddhist symbols, and the rare survival of red-coloured ink deposits in intermittent lower parts of the design, suggest that these seals were used as chops and transferred their individual designs by printing them on other materials.

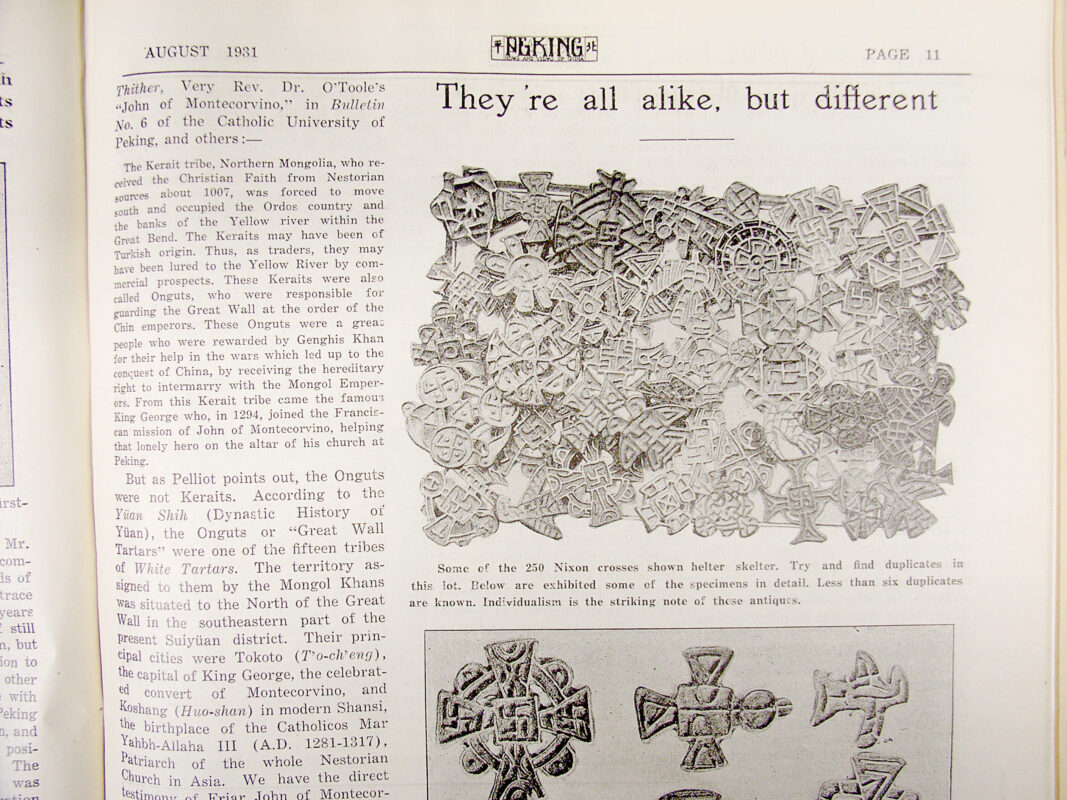

Although all crosses are cast, the Nestorian crosses all seem to be unique and are, in fact, characteristic for their individual designs (UMAG, [University Museum and Art Gallery, University of Hong Kong] official website on 7 June 2017).

The origin of Nestorianism

Wikipedia (7 June 2017) describes Nestorianism as a Christological doctrine that emphasises a distinction between the human and divine persons of Jesus.

It was advanced by Nestorius (386 to 450), the patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431, and influenced by Nestorius’ studies under Theodore of Mopsuestia at the School of Antioch.

Nestorius’ teaching brought him into conflict with other prominent Church leaders, most notably Cyril of Alexandria, who especially criticised his rejection of the title Theotokos (Mother of God) title for Mary, the mother of Jesus.

Nestorius and his teaching were eventually condemned as heretical at the Council of Ephesus in 431 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451, which led to the Nestorian Schism. Churches supporting Nestorius then broke away from the rest of the Christian Church.

Following this, many of Nestorius’ supporters relocated to the Sasanian Empire, where they became affiliated with the local Christian community known as the Church of the East. Over the next decades the Church of the East became increasingly Nestorian in doctrine, leading to it also becoming known as the Nestorian Church.

Nestorianism in China

Lo Hsing-Lin’s account of the beginning of Nestorianism in China is widely accepted now:

“With the Chinese conquest of the Eastern Turks during the reign of T’ai Tsung in the T’ang Dynasty, the Western Turks also vowed their allegiance to the T’ang Emperor. Communications with the Western Land was re-opened… It was then that a Nestorian metropolitan, Alopen, first came to China in 635AD (the ninth year of reign of Chêng-kuan). He arrived at Ch’ang-an and was well received by the Emperor T’ai Tsung who granted him permission to translate Nestorian sacred books and to spread its doctrines” (Lo, 1966, p1, in English).

The unearthing of the Nestorian Crosses in Ordos

The first bronze crosses of this kind were found in 1927, although mass unearthing did not happen until 1929, but in the study of Nestorian crosses, nobody may neglect the role played by F. A. Nixon.

Two years after the unearthing, a journalist named C. W Corman pointed out Nixon’s crucial role,

“Mr. F. A. Nixon, Postal Commissioner of Peking, is piling up the only notable collection in existence. He has more than 250 specimens on hand already and a thick file representing about all that has been written or spoken about the mystery which broke ground two years ago” (Corman, 1931, p10)

Nixon became the most significant collector, at least in terms of quantity, of the Nestorian Cross.

Chen mentioned:

“There are more than one thousand so called Nestorian Crosses, which, as a confluence, include the cross shaped pieces, the geometrical pieces, the seal shape pieces and the bird shape pieces, possessed by different museums and institutions around the world. These artefacts attract global attention due to the uniqueness endowed by their identity as Nestorian relics from the Chinese Yuan dynasty.

“The central clues in the Secret of the Mongol Cross are these: Bronze and brass crosses as large as small belt buckles have been discovered in a single district of China, with practically no trace of their existence outside that restricted area. The tokens almost without exception contain the form of the Christian cross, but fewer than six duplicates have been discovered. Each is different from the other in some minor or major detail” (Corman 1931, p10)

The participation of Nixon

The specimens intrigued Reverend Mr. Scott to such an extent that he commenced digging through the records of history and ethnology to try and trace the meaning of them.

After two years of investigation, he found himself still convinced of their Christian origin, but not yet able to prove his contention to the complete satisfaction of all other scientists, though great ones side with him.

During one of his trips to Peking he showed his crosses to Mr. Nixon. The Nixon quest for specimens was launched.

He secured the cooperation of friends in the back country and began a patient survey on his own through the curio shops of Peking, especially Mongolian agencies.

That sent the market price of the crosses sky high, from 30 cents to $20 and upwards. One adamantine dealer was holding out for $50 for each of his several items.

The news spread far inland, too, where counterfeiters were already at work casting copies of old crosses or inventing their own designs. One needs the Nixon eye and experience to detect by patina and other indications the genuineness or spuriousness of specimens (Corman 1931, p10)

According to the Yüen Shih, (Dynasty History of Yüen), the Onguts, or the Great Wall Tartars were one of the 15 tribes of White Tartars.

The territory assigned to them by the Mongol Khans was situated to the North of the Great Wall in the southern part of the present Suiyüan (now Hohhot) district.

Their principal cities were Tokoto (T’o-ch’eng), the capital of King George, the celebrated convert of Montecovino, and Koshang (Huo-shan) in modern Shansi, the birthplace of the Catholicos Mar Yahbh-Allaha III (AD 1281 to 1317), patriarch of the whole Nestorian Church in Asia (Corman, 1931, p11).’

Corman says that as far as he has been able to verify, the bronze crosses were strictly confined to the Ongut island, without a known source of inspiration. Inquiries in the far north of Siberia, to the west in Turkestan, in Manchuria, and along the routes to Central Asia reveal no connection.

Although crosses have been in existence in those places ever since the first Christian missionaries penetrated there, probably in the third and fourth centuries, they are not of the Maltese variety, with the peculiar shapes and subsidiary design of the Ordo crosses and birds (Corman 1931, p11-12).

Stylistically, all crosses fall into four different categories, many with mixed Christian and Buddhist motifs in the same artefact. The majority are executed in crucifix form – hence the group description as crosses – with either flat or round ends.

Other crosses in fact take the shape of animals, predominantly birds, but also hares and fish, as well as geometrical patterns, such as sun-like designs and miscellaneous Chinese seal-like forms (UMAG, official website 7 June 2017).

“Among them, the F. A. Nixon collection is the largest, with 979 pieces in its original paraphernalia (according to James M. Menzies), and 935 pieces presently in storage and on exhibition in the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong.

“Studies have been made of them; and conferences and other activities have been held to promulgate their significance, since Silk Road studies have been promoted to new levels during recent years” (Chen 2017, p3).

Eventually the collection of Nixon was acquired by the Lee Hysan Foundation and donated to Hong Kong University in 1961 (UMAG, official website 7 June 2017).

Just as Chen mentioned, only with systematic and rigorous interrogation can we pay the appropriate respect to the idea of Nestorian crosses.

“By eliminating unwarranted assertions, one can envisage not only the challenge, but also those elements which might eventually serve as supporting evidence for the idea” (Chen 2017, p19).

AL

ENG

ENG