China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2004/Apr

And They Shall Rise Again

Good Friday lasted a long time for the Catholic Church in China. It really started on 1 October 1949 in Tiananmen Square with the celebration of the Communist victory over the Nationalist forces. It only showed signs of a possible future resurrection in December 1978. An important meeting took place that month in Beijing. The Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party voted to implement the newly proposed open reform policy, initiating the Four Modernisations Program. The four areas of modernization were agriculture, defense, industry and science-technology. The open reform policy provided an opening for the Church to rise from the ashes of her long years of suffering and persecution. It was under the new modernisations policy, therefore, that the Church began to return to life.

Years of darkness and suffering

Throughout the years of darkness, which began in the 1950s, all churches, temples, mosques and places of worship were closed. Many of these places ended up desecrated, damaged, used as factories and warehouses or completely destroyed. By 1965, at the outset of the Cultural Revolution, the Catholic Church was extremely weak. All foreign missionaries, except Bishop James Edward Walsh of Maryknoll – and he was in prison – had been expelled, or recalled by their societies, or had left China voluntarily. Chinese bishops and priests were also in prisons or labour camps. The church had become a non-entity in Chinese society exercising hardly any influence whatsoever. For all practical purposes, it had died, and could only wait in hope for the time of its resurrection.

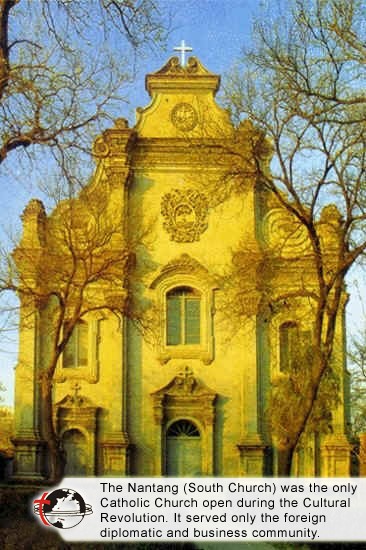

In 1971, the government did allow one lone Catholic church to open its doors. It was the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Beijing, more commonly known as the South Church or the Nantang. The Nantang is the oldest church in Beijing. The original chapel on the present site was built by Matteo Ricci in 1605. Of course, the ordinary Chinese citizen was not permitted to go to the South Church at that time. Attendance was restricted to members of the diplomatic corps and foreigners doing business in China.

New openness, new life

Perhaps the violence of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) also helped to bring about new life to the Church. As the government put an end to the follies of the Revolution and condemned the activities of the Gang of Four, it also began to restore civil order and normal activities. The Catholic Church was able to profit from this new openness.

In 1979, to succeed in its newly devised strategy of modernisation, which aimed at turning China into an advanced industrial nation by the turn of the century (2000), those in power knew that they needed the help of every able-bodied Chinese citizen. People all over China, spurred on by the promise of better days to come and a higher standard of living rallied to the Central government’s call to join enthusiastically in the reform movement.

As a result, the government asked the clergy, who were still in prisons or labour camps, to return to their churches. Bishops and priests who had suffered through the years of the Cultural Revolution, as well as those who had been in prisons since the 1950s, and who had been labelled as rightists, were exonerated and rehabilitated.

The return of the priests and sisters signalled the return of the laity. Old Catholics returned to their parishes weeping with joy, at the sight of their former aged pastor and elderly sisters. They were eager to be at Mass once again, to receive the sacraments and delighted to be able to kneel before the Blessed Sacrament to pray alone or chant their prayers with the community. These were sure signs of a possible future resurrection.

Reopening of places of Worship

Churches began to reopen one by one, at first in the large cities and then in towns and villages. In 1986, there were already 2,000 Catholic churches open in China. By 1992, that number had risen to 4,000 and today China has more than 5000. As old churches were being rebuilt, renovated or refurbished, new churches appeared almost overnight.

In 1949, when the Communists took over the country, China had a Catholic population of three million. To everyone’s surprise, during these years of persecution, the number had increased to four million. Today, it is estimated that there are as many as 150,000 adult baptisms in China every year. The total number of Catholics in China today is calculated at approximately 12 million.

Seminaries and convents reopen

The Catholic Church cannot function without the priesthood. The long years of suffering had taken their toll on China’s bishops and clergy. Some 30 years had elapsed. The men were all 30 years older than when they were put into prisons or sent to labour camps. Many had died. There were no longer any middle-aged priests and young priests were non-existent and desperately needed. Catholic seminary education had been suspended since the mid 1950s. There was an urgent need for priests and seminaries for their formation.

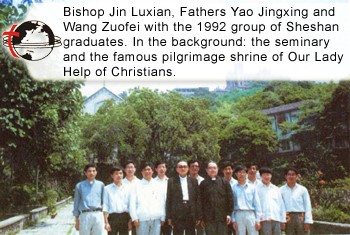

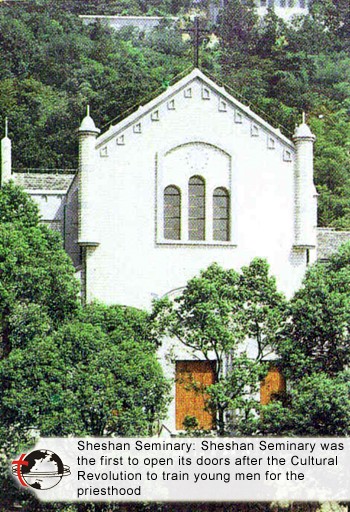

Shanghai answers the urgent call

The first area to respond to this urgent call was Shanghai. Sheshan Seminary, some 30 kilometers outside the city re-opened in October 1982. It was set up to serve the six provinces of East China. Within a short time, six other seminaries began to reopen and return to life: Beijing National Seminary, operated by the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association and the Church Administrative Committee, The Beijing Diocesan Major Seminary located outside the city, Shenyang Major Seminary located in Shenyang city, Shaanxi Major Seminary located in Xi’an, South Central China Major Seminary situated in Wuchang, and Sichuan Major Seminary in Chengdu. Soon these seminaries could boast of an enrollment of some 1,000 students preparing for the priesthood.

Today, there are 14 major seminaries operating in the official Church with an estimated enrollment of 600. The unofficial Church, which does not have seminaries in large institutional buildings has, according to reports, 10 centres for formation. These are preparing about 800 young men for the priesthood. More than 100 of those already ordained to the priesthood for the Church in China have had the opportunity to study abroad in Europe, the United States, Hong Kong, and the Philippines.

Women respond to the call

The Catholic Church throughout the ages has depended not only on priests, but also very much on women to serve the faithful in a variety of ways. Many of the women who were widely dispersed during the years of turmoil and who had remained faithful to their original vows, had returned to their parishes. Soon young women began to flock to the convents now in process of reopening, asking to be admitted to the sisterhood. This too signalled a resurrection.

Today between the official and unofficial Church, there are some 40 novitiates or centers of formation for young women throughout China. About 1,500 are presently in various stages of formation. There are some 4,000 sisters working in clinics, teaching in kindergartens, taking care of the elderly and abandoned children, helping the priests as pastoral workers, staffing retreat houses or working in the field of Catholic publications.

Today sisters are also pioneering in the field of social services in China. A special group, trained as doctors and nurses, together with a priest and a layperson are currently exploring the possibilities of caring for HIV/AIDS patients in Liaoning province. They are requesting the Shenyang diocese to open a social service agency with a special focus on HIV/AIDS. They hope to open a clinic and eventually a hospice for those terminally ill with the disease. The government estimates that there are about 1 million AIDS sufferers in China, but the United Nations gives a much higher estimate.

Healing of wounds

The wounds of the China Church’s Good Friday experience, however, are not all healed. The Catholics in China will continue to bear the stigmata for years to come. The deepest wounds are those caused by division, the lack of unity between the official Church and the unofficial Church, which constitutes a lack of oneness within the Catholic community.

This disunity is all the more painful since it is not the result of differences in doctrine, but rather the result of political constraints. These political constraints, in turn, cause the faithful to be separated from the Vicar of Christ, Our Holy Father who, as head of the Church, is constantly being reminded not to interfere into China’s internal affairs.

Thousands also bear the wounds of long imprisonments, house arrests, surveillance, humiliation, accusations and all manner of harassment. Many have lost as many as 40 years of their lives languishing in prisons or labour camps. This situation saps a great deal of physical and spiritual energy.

When the Lord rose from the dead on Easter Sunday, he had not shed his wounds. They were part of his crown and glory. They were a reminder to those who would later follow him that he had not suffered in vain. In their imitation of Christ, our Catholic brothers and sisters in China are also a sign that their wounds and suffering have not been in vain.

The wounds of the resurrected Christ also sealed the faith of a doubting disciple: “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.” Later Jesus said to Thomas, “Put your finger here and see my hands, reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt, but believe.” (Jn. 21:25, 27.) The resurrected Lord is asking the Catholics in China to believe that their wounds will bring total healing to their Church.

When the Church in China is free to accept the gift of Christian unity, it will then truly have risen from the ashes of its many deaths and dyings.

ENG

ENG