China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2005/Apr

The pope speaks to China

An Interview with Father Elmer Wurth, MM

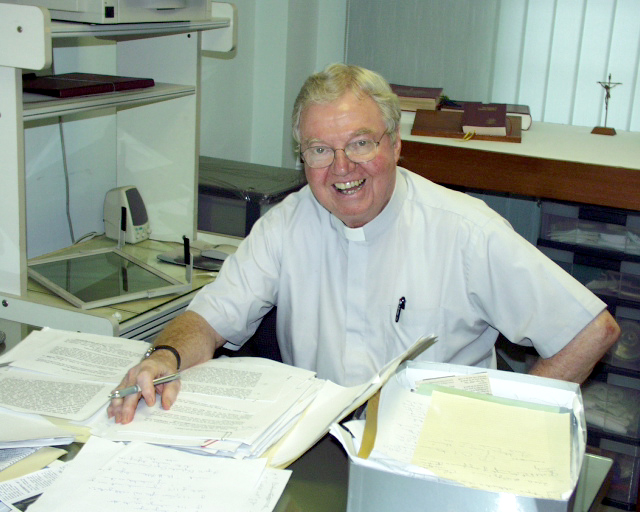

Father Elmer Wurth has worked at the Holy Spirit Study Centre, Hong Kong, since 1980, and has done an invaluable work in the field of documentation. His outstanding contribution has been the gathering of papal statements dealing with the New China. In 1985, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York, together with the Holy Spirit Study Centre in Hong Kong, published a volume, edited by Father Wurth, entitled: Papal Documents Related to the New China. These documents covered the period from 1937 to 1984.

Since that time, Father Wurth has assiduously followed, collected and analysed Pope John Paul II’s statements on China. The second volume of papal documents will deal entirely with John Paul II’s pontificate. The Holy Spirit Study Centre hopes to have this second volume ready by the end of the year. The pope’s death brings to a close his unceasing, untiring and seemingly unsuccessful efforts to bring about unity in the Church in China and reconciliation with the Chinese government. The resolution of these two thorny problems is now left to a new pope.

Following is an interview with Father Wurth conducted by the editor of China Bridge, Maryknoll Sister Betty Ann Maheu, following the death of our Holy Father, John Paul II.

Q: Father Wurth, you have faithfully followed and recorded all of our Holy Father: John Paul II’s statements on China since he became pope on 16 October 1978. Would you say that at the beginning of his pontificate the Holy Father was hopeful about effecting reconciliation between the Vatican and Beijing?

A: His early statements revealed that he was very hopeful that he would be able to make a breakthrough in the strained relations that had characterised Sino-Vatican relations since 1951.

He immediately made overtures of friendship and showed an understanding for China’s unique situation. During his 26-year reign, he made no fewer than 30 important references to China, each one an expression of his deep love and concern for the Chinese people.

Q: Pope John Paul II became pope in October of 1978. When did he first address the Chinese people?

A: He first mentioned China on Sunday, 19 August 1979, during the weekly recitation of the Angelus. The message he wanted to give from the outset was that China is never absent from his prayers.

He was hopeful about China’s new openness and he wanted to stress that the bond of love between Chinese Catholics and the Holy See had never been broken. He was telling them that he was with them in his heart and in his prayer. And he referred to them as “the great Chinese people,” a phrase that he would repeat often during his pontificate.

Q: On several occasions the Holy Father expressed his desire to meet the Chinese people directly and on their own soil. Would you comment on this often-expressed wish?

A: The fact that the Holy Father was not able, personally, to go to China and meet and speak directly with the Chinese people was a great disappointment to him. He wanted to convey, personally, to the Chinese his sentiments of respect and love. Not being able to realise this desire was certainly a cross very difficult to bear.

Pope John Paul II was a pope of unity. He knew that unity within the China Church and unity with Rome depended greatly on the possibility of everyone in China being able to enjoy full religious liberty. In one impassioned plea he prayed, “O hearts of our brothers and sisters in the far-off land of China! Be united with us in this Sacrifice of Redemption, as we are united with you.” He wanted the Church in China to be one and read every little sign of hope as positive developments.

Q: In the introduction to the second volume of your work, you mention overtures of friendship, assurances of prayers and love for the people. What other concerns did the Holy Father express in relation to China?

A: He has often expressed concern for peace in the China Church and, of course, the desire that the entire Catholic community would be completely free to rejoin the Universal Church. This division, imposed politically, weighed heavily on the Holy Father throughout the whole of his reign.

Q: Over 150 countries around the world have established normal diplomatic relations with the Vatican. Why is it so difficult for Rome and China to do this?

A: The difficulty lies in the fact that both sides have set up pre-conditions that the other must meet before any progress can be made. I will only give a couple of examples. The pope expects to be allowed to choose and contact his own bishops. The Chinese government considers this to be interference in its internal affairs. The government feels it alone has the right to control all aspects of the citizens’ life.

Then there is the Vatican’s relation with Taiwan. The Vatican has already downgraded its diplomatic status, but China demands total abandonment of diplomatic relations. In spite of strained relations, I am still optimistic and hopeful that these issues will be resolved.

The new pope’s statements on China during the first few months of his pontificate could offer a wonderful breakthrough. He may be able to establish dialogue with Chinese leaders if he accepts that China has changed dramatically and now occupies a leading political role on the world scene.

Q: Throughout the years of John Paul’s pontificate, the Vatican seems to have misread some of China’s attitudes. I am thinking of their reaction to the appointment of Bishop Tang as Archbishop of Guangzhou, for instance. Would you comment?

A: Yes, on several occasions when Rome felt that it was honouring China, China again reverted to the idea that Rome was interfering in its internal affairs. The situation of Bishop Tang was particularly painful since Rome wanted to reward a man who had suffered long for his faith and he ended up not being able to return to his diocese. There was also the case of Bishop Ignatius Gong Pinmei, who was made a cardinal in pectore. This also displeased China.

In more recent years relationships became very strained after the canonisation of the China martyrs. In speaking about these canonisations, the Holy Father said, “With this canonisation, the Church most certainly does not want to pass an historical judgment on those years and still much less to legitimise some of the conduct of the government of the time that weigh heavily on the history of the Chinese people. On the contrary, the Church wishes to show the heroic fidelity of these worthy sons and daughters of China, who did not allow themselves to be intimidated by the threats of a cruel persecution.” So what was meant to be an honour was construed by China to be totally blameworthy.

Q: Throughout his life as head of the Catholic Church, the Holy Father has often encouraged the faithful “not to be afraid.” Like Jesus he often repeated, “Fear not!” How did he himself set an example of fearlessness?

A: The Holy Father always spoke his truth without fear when this truth may not have been popular with many around the world.

He will long be remembered for his respect for human life. He consistently spoke strongly against abortion, and the death penalty. His unbending position on these two life issues certainly could not have pleased China.

In line with his culture of life, he was strongly opposed to war for solving enmities between nations. When the war between China and Vietnam escalated in 1979, he said, “Anyone who shares Christ’s love for men cannot but be saddened and tremble at the lives that are sacrificed or in danger and at the sufferings and hardships of combatants and populations. I am thinking in particular of children, the old and the sick.” He also spoke out fearlessly against the US War with Iraq. He made an unpopular decision when he denied women the possibility of ordination. Many women openly disagreed with him. Not only was he not afraid to make unpopular choices, but he also had the courage of his conviction to admit that some choices made by previous Catholic leaders had been wrong and had hurt many people.

He often tried to reassure the Chinese authorities that there was no dichotomy between being authentically Chinese and authentically Christian. “The civil authorities of the People’s Republic of China should rest assured: a disciple of Christ can live his faith in any political system, provided there is respect for his right to act according to the dictates of his own conscience and his own faith… The Chinese nation has an important role to play in the international community. Catholics can make a notable contribution to this, and they will do so with enthusiasm and commitment.”

Q: What, in your opinion, would best characterise Pope John Paul’s wish for the Chinese people?

A: I think I would answer your question with a quote of the Holy Father spoken on 6 May 1984, in Korea: “May the great and wise people of China…seek as true Chinese, to live that faith in full communion with the Universal Church, to the joy and enrichment of all.

ENG

ENG