China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2011/Nov

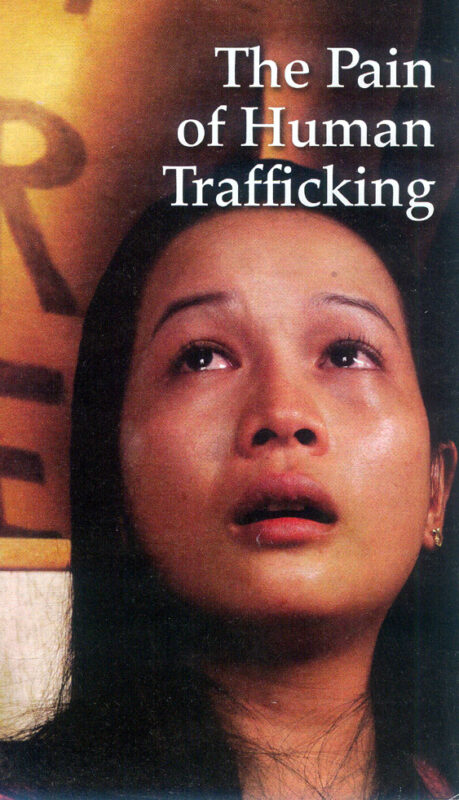

Human trafficking

One hundred and forty six countries are signatories of the United Nations (UN) Palermo Protocol, which was adopted in December 2000 and came into force in September 2003.

Over the past decade, they passed laws banning human trafficking. Most nations no longer deny that this crime still exists and have, instead, adopted a wide range of policies and partnerships.

Unfortunately, human trafficking is a multi-billion dollar industry and much needs to be done to eliminate this form of slavery.

Involuntary servitude

Forms of human trafficking include forced labour, or involuntary servitude, which happens when unscrupulous employers exploit workers, who become more vulnerable because of high rates of unemployment, poverty, crime, discrimination, corruption, political conflict or cultural acceptance of the practice.

Immigrants are particularly vulnerable, but individuals also may be forced into this situation in their own countries.

Female victims of forced or bonded labour, especially women and girls in domestic servitude, are often sexually exploited as well.

Sex trafficking

Sex trafficking happens when a person is coerced, forced, or deceived into prostitution, or maintained in prostitution through coercion.

Everyone involved in recruiting, transporting, harbouring, receiving or obtaining a person for that purpose has committed a trafficking crime.

Sex trafficking can also occur within the context of debt bondage, as women and girls are forced to continue in prostitution through the use of unlawful debt, purportedly incurred for their transportation, recruitment, or even their crude sale, which exploiters often insist must be paid off before they can be freed.

It is critical to understand that a person’s initial consent to participating in prostitution is not legally determinative: if they are thereafter held in service through psychological manipulation or physical force, they are trafficked victims and should receive benefits outlined in the UN protocol and applicable domestic laws.

Bonded labour

Another form of force or coercion is bonded labour, or the use of a bond or debt. Often referred to as debt bondage, the practice has long been prohibited and the UN protocol requires has been criminalised as a form of trafficking in persons.

Workers around the world fall victim to debt bondage when traffickers or recruiters unlawfully exploit an initial debt assumed by the worker as part of the terms of employment.

Debt bondage among migrants

Among migrant workers, abuse of contract and hazardous conditions of employment do not necessarily constitute human trafficking.

However, the imposition of illegal costs and debt in the source country, often with the support of labour agencies and employers in the country of destination, can contribute to a situation of debt bondage.

This is the case even when the worker’s status in the country is tied to the employer in the context of temporary, employment-based work programmes.

Involuntary domestic servitude

A unique form of forced labour is the involuntary servitude of domestic workers, whose workplaces are informal, connected to their off-duty living quarters and usually not shared with other workers.

Such an environment, which often isolates them socially, is conducive to non-consensual exploitation, since authorities cannot inspect private property as easily as they can formal workplaces. Investigators and service providers report many cases of untreated illnesses and tragically, widespread sexual abuse, which in some cases may be symptomatic of involuntary servitude.

Forced child labour

Most international organisations and national laws recognise that children may legally engage in certain forms of work.

There is a growing consensus, however, that the worst forms of child labour, include bonded and forced labour.

A child can be a victim of human trafficking regardless of the location of that non-consensual exploitation.

Indicators of possible forced child labour include situations in which the child appears to be in the custody of someone who is not a member of the child’s family, who has the child performing work that financially benefits someone outside the family and does not offer the option of leaving.

Anti-trafficking responses should supplement, not replace traditional actions against child labour, such as remediation and education.

When children are enslaved, their abusers should not escape criminal punishment by virtue of long-standing administrative responses to child labour practices.

Child soldiers

This manifestation of human trafficking involves unlawful recruitment or use of children through force, fraud, or coercion as combatants or for labour, or for sexual exploitation by armed forces.

Perpetrators may be government forces, paramilitary organisations or rebel groups.

Many children are forcibly abducted to be used as combatants. Others are unlawfully made to work as porters, cooks, guards, servants, messengers or spies.

Young girls can be forced to marry or have sex with male combatants.

Both male and female child soldiers are often sexually abused and are at high risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

Child sex trafficking

According to the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), as many as two million children are subjected to prostitution in the global sex trade. International covenants and protocols obligate the criminalisation of sexual exploitation of children.

The use of children for commercial sex is prohibited under the UN protocol, as well as by legislation in countries around the world. There can be no exceptions and no cultural or socio-economic rationalisations preventing the rescue of children from sexual servitude.

Sex trafficking has devastating consequences for minors, including long-lasting physical and psychological trauma, disease (including HIV/AIDS), drug addiction, unwanted pregnancy, malnutrition, social ostracism and possible death (cf. United States of America Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2011 [TIP]).

The latest US State Department statistics say many as 100,000 people in the US are in bondage and perhaps 27 million people worldwide (New York Times, July 4).

The government of Hong Kong insists that the city is not a centre for forced prostitution, but social workers say the misery persists.

Social workers, who deal with the broken people sex-traffickers leave in their wake, many from Asia and Africa, have voiced concerns that the political will to tackle the problem is not present.

In the 2011 Trafficking in Persons Report, Hong Kong is described as “a destination and transit territory for men and women from mainland China, The Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Nepal, Cambodia and elsewhere in southeast Asia, subjected to forced prostitution and possibly forced labour.”

The report also says that Hong Kong “does not fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking; however, it is making significant efforts to do so,” referring to the city’s inter-departmental Anti-Trafficking Working Group (South China Morning Post, July 17).

This July, the police in Guangzhou cracked a huge human trafficking operation. A total of 89 kidnapped infants were rescued and 369 suspects arrested in two major trafficking cases.

A major channel used to abduct and sell children from Vietnam to China and a big criminal network was destroyed. Most members of the criminal gang were Vietnamese residents.

In another case, on July 21, police authorities in 14 provinces and autonomous regions dispatched some 2,600 officers to crackdown on a giant cross-region trafficking group of 330 offenders.

A total of 81 infants was rescued in this case. Most of the children were baby girls, aged from 10-days to just four-months-old.

They are now being cared for in various institutions (China Daily, July 27).

Sex slave dungeon photos

Police in Henan recently revealed grisly details of life in a cellar and how four kidnapped women allegedly helped a 34-year-old ex-fireman, Li Hao, kill one of the captives.

The photos show the dungeon in which six women were held as sex slaves for up to two years.

Some of the women were forced to help dig their own prison, a dungeon six metres underground, below a cellar, where they were confined in unhygienic conditions. They were locked behind several metal gates to block their escape.

Li Hao raped, tortured and forced them into prostitution. At the time of his arrest, the four surviving women had been charged with helping the man kill one of two fellow prisoners, who died in the dungeon.

The two women were tortured and strangled by Li when they tried to leave.

He buried them in the basement. Li Hao was arrested in early September and faces charges of murder.

The fate of the women is unclear (South China Morning Post, September 30).

Young boys in many parts of the world dream of one day becoming famous football stars. Unfortunately, there are also people waiting to exploit their youth and inexperience.

In a recent report, a Frenchman was arrested for trafficking young boys for homosexual prostitution.

The man travelled to many countries in Africa and made friends with young boys and told them and their families that he could arrange for them to receive training in famous football clubs.

He then arranged for them to be sent to different parts of Africa and even Europe.

When the boys got to their destinations, they were told they would have to do some work first and were turned into sex slaves.

They never saw a football club. Fortunately this Frenchman was arrested and some of the boys were rescued and told their stories (BBC, October 20).

As Christians, we must be aware of and learn more about the crime of human trafficking and do whatever we can to stop it.

Ecclesiastes 4:1 says, “I looked and saw all the oppression that was taking place under the sun: I saw the tears of the oppressed and they have no comforter; power was on the side of their oppressors and they have no comforter.”

May the Holy Spirit help us to be comforters of the oppressed in our day.

MC

ENG

ENG