China Bridge (神州橋樑)_2019/Apr

The May Fourth Movement and its impact on Catholic education in China

The May Fourth Movement and regaining the right to education

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement. It not only affected the political environment in China, but also brought about profound changes in literature and social life. One aspect that was deeply affected was education in China.

The movement had two rallying cries: Democracy and Science. This clamour heightened the concern of the Chinese people over the system of modern education.

Against a background of the rise of Japan, a humiliating Versailles Treaty that granted Shandong, a former German concession, to Japan, it consequently propelled the movement of “regaining the right to education” in the 1920s, which aimed at eliminating foreign as well as Christian influence on education in China.

On 9 March 1922, students in Shanghai organised the Anti-Christian Movement Student League (非基督教學生同盟). That spring, Professor Cai Yuanpei, renowned educator who, as president of the Peking University, had defended his students from government retaliation after the demonstrations, made a speech at the Peking Anti-Religions League.

He reaffirmed that (1) theology at universities should be replaced by the History of Religions and Comparative Religion within the Department of Philosophy. (2) School curricula should not distribute religious dogma, nor should there be prayer ceremonies. (3) Foreign missionaries should no longer participate in education work.

The 1924 Shanghai Synod and its education policy

Facing a series of challenges, the Catholic Church found it necessary to devise a suitable policy on education work. In 1924, the first Apostolic Delegate to China, Archbishop Celso Costantini, hosted a synod in Shanghai. A total of 43 bishops, three perfects apostolic and 27 superiors of religious congregations attended.

In the final report, The First Chinese Council in 1924: Acts, Decrees, Norms and Regulations, section VII is on Colleges and Schools. The section on education consists of seven chapters. Article 749 reads as follows:

For many years, Catholic schools have played an important and valuable role. But the Chinese government is about to formulate a new policy regarding these schools. If we do not take part in education, the situation will become adverse to us. We also do not have a reason not to participate. So we should try our best to let our work shine, so that the seeds of Christ’ salvation can be sown on the soil of new life.

On the other hand, participants of the synod were alerted to the challenges posed by the new trend. Article 756 reads:

The Mother Church urgently imparts these directions because the government is establishing more and more schools and keeps on filling the minds of young students with materialism. This is appalling. The young will lose traditional life principles, and blindly chase what is new. The fact is clear that anti-religion schools are full of anti-Catholic ideology, with a bias toward rationalism.

In 1924, the Students’ Association of Kwangtong Province (廣東省學生會) established a commission of the movement to regain the right to education (收回教育權運動委員會). Among its injunctions: “Schools run by foreigners should not include evangelisation in the formal curriculum. They cannot force students to worship or to read the Bible.”

Although the commission referred to “foreigners,” they were actually pinpointing Christians. Afterwards, even schools run by Chinese Christians were prohibited from promoting religion.

The national government was under pressure from intellectuals to take back the control of Church-run schools. But the Shanghai Synod asked local bishops to firmly control the personnel of schools. Article 769 reads: “The management and staff of the schools should be assigned by local bishops, with the advice of the Board of Diocesan Advisors.”

Pressure from the national government on Church education work

In April 1929, the National government promulgated the Religious Groups and the Establishment of Education Works (「宗教團體與興辦教育辦法」) to regulate the education of Church-affiliated schools. In 1933, the government amended the regulations to “the Rule of Private Schools” which included the following:

Article 6: Foreigners are not allowed to set up primary schools for Chinese children.

Article 7: The principals of private schools should be full-time professionals, and should not concurrently hold another position.

Private middle schools and above that are founded by foreigners should have a Chinese principal or rector.

Article 14: … In extraordinary circumstances when foreigners are to be appointed as board members, that number should not exceed one-third and the Director of the Board should be Chinese.

On 3 September 1934, the Education Department of the national government went further and promulgated the Order to Restrict the Establishment of Schools by Religious Groups (限制宗教團體設立學校令).

Catholic education carried on amidst travails

Despite all the tensions, Catholic education in China kept developing. In 1936, there were 420,000 students at different levels of schools. Professor Lai Zhen Pu compiled the following figures:

Universities: Three

Boy’s Middle Schools: 58 with 3,469 Catholic students and 7,868 non-Catholic students.

Girl’s Middle Schools: 40 with 2,538 Catholic students and 4,729 non-Catholic students.

Boy’s Higher Primary Schools: 266 with 8,034 Catholic students and 3,114 non-Catholic students.

Girl’s Higher Primary Schools: 184 with 4,385 Catholic students and 4,861 non-Catholic students.

Boy’s Elementary Primary Schools: 2,719 with 58,223 Catholic students and 46,009 non-Catholic students.

Girl’s Elementary Primary Schools: 1,114 with 28,544 Catholic students and 22.495 non-Catholic students.

Kindergartens: 11,827 with 126,534 boy students and 106,241 girl students.

Obviously, the policy of limiting Church education work was not very successful. While the government would like to have deterred Christian groups from the field of education in China, they did not invest enough to fill the vacuum. In April 1933, the government released the following figures: out of 41.441 million school-aged children, only 7.118 million were in school.

The illiteracy rate was as high as 82 per cent. In remote rural areas, in particular, the government had no money or expertise to provide basic education. So they turned a blind eye to Christian-run schools. It was not until after World War II that the government implemented strict policies against education work by religious groups.

Did the Church enjoy greater freedom during the Qing Dynasty?

After the opium wars, in the second half of the 19th century, the Qing government paid almost no attention to Christian schools in China. The Catholic and Protestant Churches were free to administer the education systems they wanted.

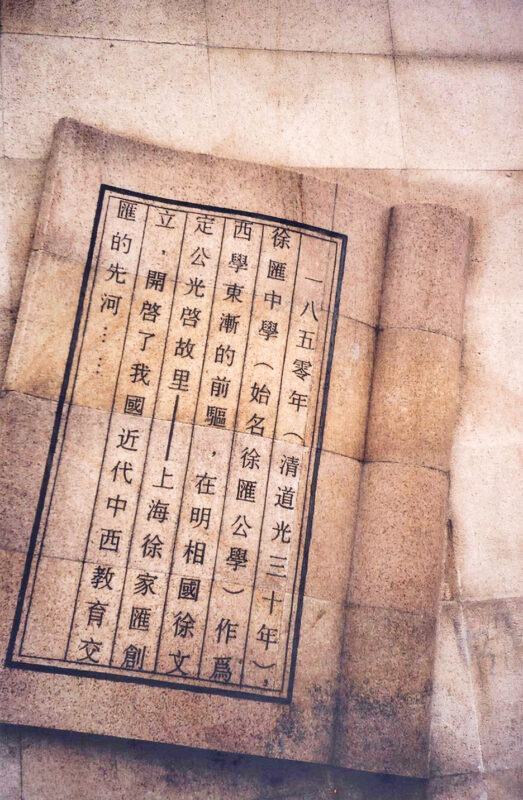

A tablet outside St. Ignatius College (徐匯公學) recorded the beginning of Catholic education work in modern China. It reads:

In 1850 (the 30th Year of Daoguang Emperor), Xuhui High School (originally called St. Ignatius School) was established in the hometown of His Excellency Xu Guangqi, a prime minister of the Ming Dynasty. It was a vanguard of introducing western education to the east, and a forerunner of the confluence of Chinese and western education in contemporary China.

One important reason why the Church was left alone in the 19th century to found and run schools was that the government were recruiting high ranking officials through the Imperial Examination System (科舉制度). Those who entered Church schools would never sit for the Imperial Examination.

In 1905, however, following the abolition of the Imperial Examination System and the introduction of modern education, the situation changed. After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, the national government further promoted western education. In this context, Church schools became more attractive as they excelled in teaching foreign languages (English and French especially) and modern science.

Foreign missionaries were eager to run schools, not to enter into competition with local intellectuals. They were there because they recognised the great need for schools in China.

It was understandable, but unfortunate that intellectuals during the May Fourth Movement, wanted to expel foreign missionaries from China’s education system. The anti-Christian education policies continue to this day.

Anthony Lam

ENG

ENG