CHINA-VATICAN

TThe Jesuit missionary from Macerata inaugurated an era that lasted for centuries and helped China to modernize and emerge from isolation. The 800 missionaries – including those from PIME – brought Western medicine, hospitals, girls schools, new agricultural crops, universities to China. Why Xi is not going to the Vatican. During the Cultural Revolution, the left-wing Italian parties praised Mao, hiding his massacres and failures. The fragility of Xi Jinping, opposed in China by the “leftist” fringes.

by Bernardo Cervellera

03/20/2019, 13.26

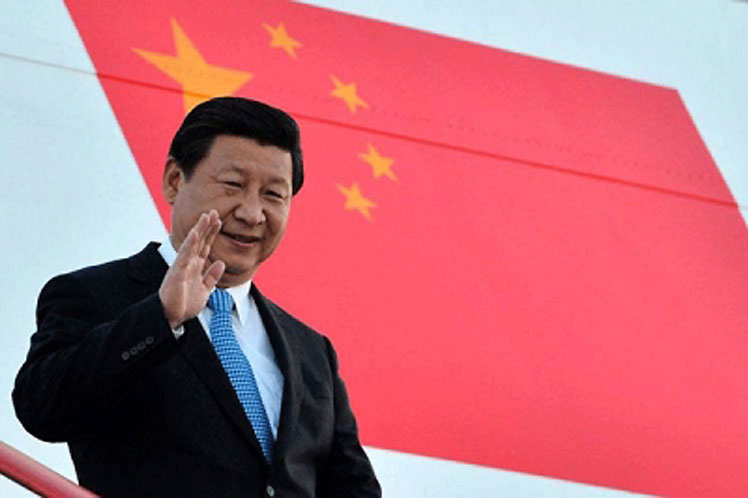

Rome (AsiaNews) – In an interview given today to the Corriere della Sera, on the eve of his journey that will take him to Rome, Monaco and France, President Xi Jinping’s words are a true love song for Italy. Yet what is really amazing about this long ode to relations between our nation and the Middle Empire is his silence on Matteo Ricci and the Cultural Revolution.

Xi lists the relations between the two “ancient civilizations” citing Virgil, Gan Ying, Marco Polo’s Million, … However, he remains completely silent about the Italian Jesuit from Macerata who at the end of the sixteenth century, armed only with his humanistic and religious culture, succeeded in presenting himself before the emperor and getting himself hired as a court astronomer. He inaugurated an era lasting centuries in which the Jesuits – many of them Italians like Giulio Aleni, Martino Martini, Giuseppe Castiglione – helped China to reposition itself in the world of that time after the isolation sought by the Ming dynasty, helping the empire to modernize in science, agriculture and even the art of war.

The Italian missionaries of the nineteenth century – including those of the PIME – who have brought Western medicine, hospitals, schools for girls, new crops to satisfy the hunger of the Chinese as well as universities are absent. It is true: the green light for evangelization came from the impositions of Western powers with unequal treaties. But it is also true that the missionaries did not stay around to dabble in foreign territorial concessions, but reached the most abandoned and inaccessible places of the empire to bring aid, culture, solidarity together with faith. The love of missionaries towards the Chinese, more than towards their homelands, is evident in Msgr. Simeone Volonteri (1873-1904) from PIME, who along with other Italian missionaries refused the “protectorate” of Italy. After the Boxer nationalist uprising, they also refused the “war booty” guaranteed to them by Italy’s victory, asking it be used for charity work for the benefit of the Chinese[i]. For his clear testimony, Msgr. Volonteri received the title of “Great Mandarin of the Chinese Empire” from the emperor.

Xi Jinping’s silence on these facts shows a lack of historical knowledge or – more likely – an ideological vision of history. From Mao onwards, religion and Catholicism in particular have been branded as “servants of imperialism” in China, only to mimic the Soviet Union that had engaged in a furious war against religions.

This ideological vision – the religion that is the source of all possible evils – is still present in China, supported by the most radical wing of the Party, which lurks in the United Front and in the State Administration for Religious Affairs. This more radical wing is the enemy of the agreement signed by the Vatican and China and continues to oppress bishops, priests and faithful with its ideology of an “independent Church”, even if the agreement admits that the Pope is the head of the Catholic Church in China. If Xi Jinping, coming to Italy, does not visit the Vatican – as is the case for all heads of state in the world – it is only because he does not want to be “overtaken on the left” by this ideological fringe, which uses religion also in its battle against the president.

The same can be said for the silence on the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). At that time, Italy and the Italian communist party became the greatest defenders of the Chinese experiment in Marxist extremism. Politicians, groups, demonstrations in Italy hailed China and its revolution as “the workers’ paradise”, the “place of justice”, and Mao Zedong as the benevolent god who offers his pearls of wisdom to nurture the new world.

Instead, with the civil war he incited, Mao tried to hide the failures of the Great Leap Forward (which caused about 50 million deaths, almost all of them from hunger), by eliminating his personal enemies. In this case the historical myopia was above all on the part of Italy and of the leftwing parties, which paraded around with luminous images of the revolution, sweeping blood and dust of the Chinese themselves under the carpet. And they never acknowledged a “mea culpa”.

However in China, even now – and at the behest of Xi Jinping – this period of “great chaos” cannot be studied or judged: “perestroika” is forbidden for fear that it will lead to the same result as the USSR: the fall of the Chinese Party communist. Perhaps the prohibition is also due to the fact that too many things in China – media control, dissidence, religions, foreign trade – have an air of Cultural revolution.

As in all violin solos the silences further enhance the fullness of the melody. In Xi’s article, these silences tell instead of the weakness of his position, halfway between a “siren song” – to push Italy into a partnership with Beijing, without the European Union – and a cry for help to support his image, dangerously threatened at home by the “leftist” enemy fringes.

ENG

ENG